In the IT world, the concept of “cloud repatriation” is increasingly gaining traction, meaning the move from the cloud back to on-premises or private infrastructures.

For some time now, we have been keeping an eye on this trend, which has been widely discussed overseas for quite a while.

According to what was published in a Sole 24 Ore Cloud article, rising costs are pushing companies toward hybrid data management, and we have started to study the reasons in order to fully understand the dynamics.

What are the reasons that drive companies to return to the on-premises model, and when does it make sense to do so?

Cloud Repatriation: the Return of On-Premises as a 2026 Trend

Several recent studies indicate that this phenomenon will be a macro trend in 2026, partially reversing the “everything in the cloud” approach that has characterized recent years. According to an analysis by TechRadar Pro, “cloud repatriation” could become one of the hottest terms of 2026.

These are not isolated cases: a 2024 Barclays survey found that 83% of CIOs expect to bring at least part of their workloads back from the cloud to their own systems within the year.

At the same time, IDC estimates that about 80% of companies are planning some form of “return” of compute or storage resources in the short term.

In short, the pendulum that in the 2010s pushed everything toward the public cloud may now be swinging back toward hybrid and private solutions.

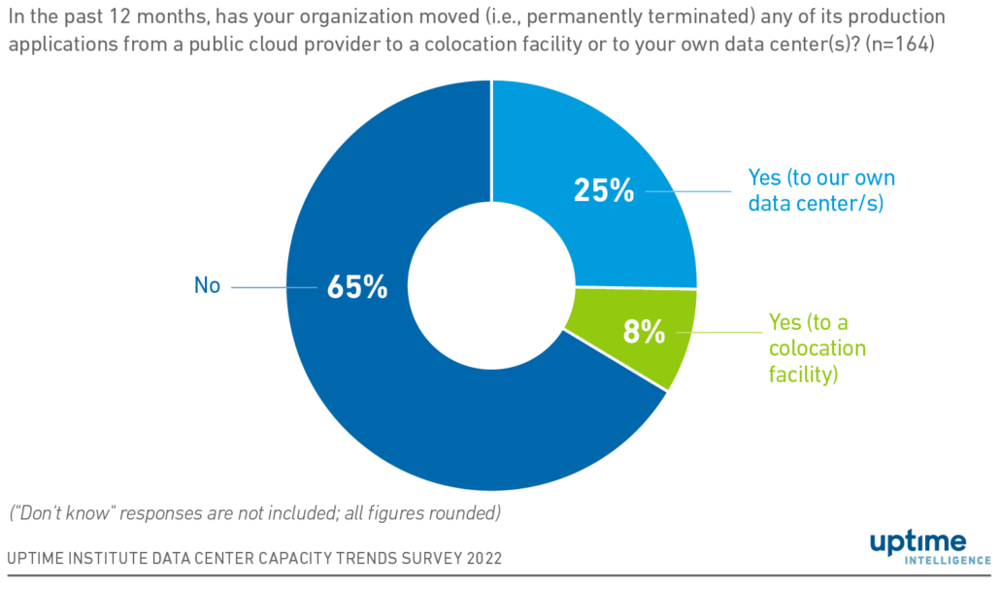

Figure 1: Percentage of organizations that have moved production applications from the public cloud to their own data centers or to colocation facilities (33% overall). Data from the Uptime Institute survey.

1. Is Cloud Repatriation the Only Alternative?

According to available analyses and data, full repatriation remains an exception: a 2024 survey shows that only 32.6% of applications hosted in the public cloud are brought back in-house, mainly as individual workloads.

The main drivers are performance and, secondarily, security. However, repatriation is technically and strategically complex and requires in-house expertise.

2. Why Cloud Repatriation? The Reasons for Returning On-Premises

After more than a decade of a “cloud-first” strategy, many companies have started asking: which workloads are truly suitable for the public cloud, and which are not? The reasons driving a return to on-premises are varied and often occur simultaneously:

- Unpredictable and Higher-than-Expected Costs: the cost-effectiveness of the cloud has often not materialized. Due to excess capacity charges, data egress fees, storage, and always-on resources, cloud bills can exceed expectations.

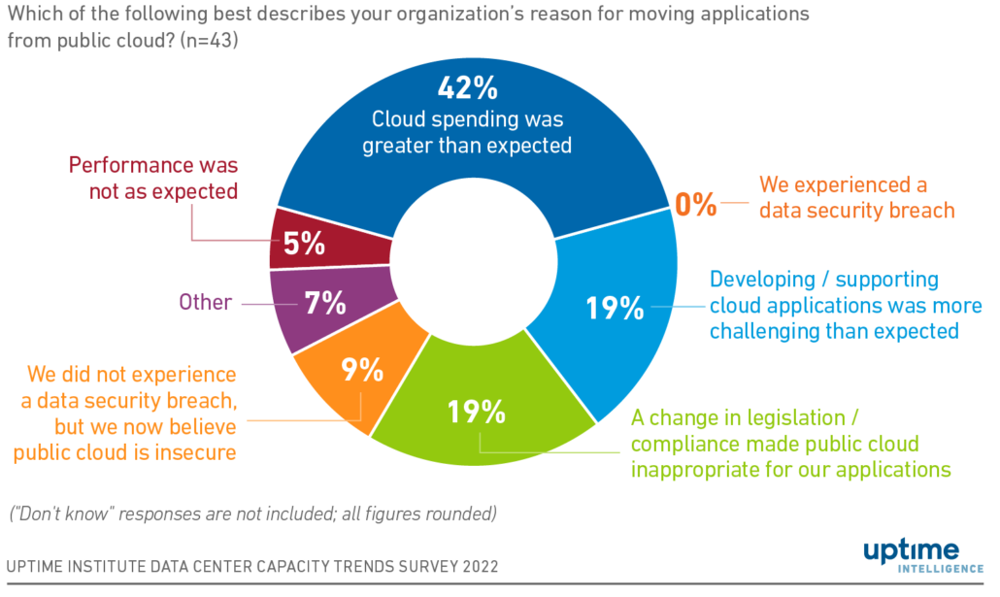

In a survey, 42% of companies that repatriated workloads reported that their cloud spending was higher than expected.

This leads many organizations to consider it more cost-effective to invest in their own infrastructure, with more predictable costs and direct control.

- Vendor Lock-In and Architectural Flexibility: building everything around a cloud provider’s proprietary services can tie a company’s hands (lock-in). The risk increases if the provider changes prices, terms, or technologies. Many readers know exactly what we’re referring to.

We all clearly remember the VMware–Broadcom situation, and even though it happened in a context not directly related to this topic, the chaos it caused was truly disastrous for some organizations.

Returning to on-premises or colocation infrastructure restores full control over the software stack. Companies can freely choose open-source tools, change DevOps pipelines, orchestrators, hypervisors, etc., without being locked into a single vendor’s ecosystem.

- Data Sovereignty, Privacy, and Compliance: entrusting critical data to public clouds raises questions about where the data physically resides and who has access to it. With increasingly strict data protection regulations (GDPR, NIS2, DORA, industry-specific rules like HIPAA, PCI-DSS, etc.), companies worry they may not be able to ensure full compliance if their data is hosted by global providers.

Some hyperscalers have admitted they cannot guarantee that data will always remain within specific jurisdictional boundaries. This has fueled a return to on-premises or private cloud solutions to maintain control over sensitive data and avoid legal risks.

- Security and Control: even without experiencing actual data breaches in the cloud, many organizations perceive on-premises infrastructure as more secure, or at least more consistent in management.

Using multi-tenant cloud services and heterogeneous proprietary tools can complicate visibility and the consistent application of security policies across hybrid environments. Bringing systems back in-house allows companies to standardize security measures and reduce dependence on third parties for critical aspects.

- Performance and Latency: for low-latency, high I/O applications (e.g., financial databases, real-time systems, gaming) or those requiring specialized hardware (GPUs for AI, etc.), the public cloud can introduce too much variability and overhead.

Repatriating these workloads to dedicated hardware allows for more stable performance and lower response times, thanks to physical proximity to users and the absence of “noisy neighbors” typical of multi-tenant cloud environments.

It should be noted that the public cloud remains irreplaceable in certain scenarios—for example, for some services, startups, or projects with initially unpredictable workloads, where on-demand scalability is vital.

As the venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz ironically noted, there is a “cloud paradox”: “You’d be crazy not to start in the cloud; but you’d be just as crazy to stay there forever.”

Many companies, after using the cloud to grow quickly, reassess the cost-benefit balance once they reach a certain scale, combining the cloud with their own infrastructure, which is more cost-effective and controllable over the long term.

Figure 2: Main reason for cloud repatriation cited by organizations. Excess/unexpected cost ranks first (42% of responses), followed by compliance (19%) and cloud development complexity (19%). None of the respondents cited a security incident as a direct cause.

3. Examples of Companies That Have Left the Cloud (and Why)

In recent years, several notable cases have emerged of companies—both large and small—that have reversed course, moving from public cloud infrastructure back to on-premises or hybrid solutions.

Below are some significant examples (large and well-known companies), along with the stated reasons and benefits they achieved:

| Azienda | Azienda | Risultati ottenuti |

|---|---|---|

| 37signals (Basecamp/HEY | Unsustainable cloud costs for stable workloads; complexity not reduced compared to on-premises. | –60% reduction in cloud spending (from $3.2M to $1.3M/year; estimated savings >$10M over 5 years by bringing services back in-house). Simplified infrastructure and greater control. |

| GEICO (insurance sector) | Cloud spending increased 2.5× over 10 years (over 600 apps migrated); issues with availability and technological lock-in. | Initiation of repatriation for many workloads. Implementation of an internal private cloud (OpenStack + Kubernetes) to improve performance and reduce recurring costs. Greater technological autonomy. |

| Dropbox | Increasing cost of public cloud storage as user data grows. | Migrated ~90% of customer data to proprietary hybrid infrastructure as early as 2016.

Estimated $75 million saved over two years thanks to private data centers. Unit storage costs drastically reduced at scale. |

4. So, is the Public Cloud dead?

Absolutely not! On the contrary, in recent months there has been persistent talk of a return to on-premises, but The Stack explains that these claims are probably exaggerated.

In fact, Gartner predicts that global spending on public cloud services will grow from $595.7 billion in 2024 to $723.4 billion in 2025, an increase of over 20%.

The adoption of artificial intelligence and the spread of distributed, cloud-native, and multi-cloud infrastructures are driving more companies to use the public cloud, resulting in an expected growth rate of 21.5%.

5. What’s the Future? Hybrid Cloud: a Winning and Balanced Approach

Analysis of these trends shows that the future of enterprise IT will be increasingly hybrid. Few companies intend to give up the public cloud entirely; rather, the goal is to optimize the mix of resources.

According to Gartner, by 2027, 90% of organizations will adopt multi-cloud and hybrid strategies. This means harmoniously integrating public clouds, private clouds, and on-premises infrastructure, selecting the optimal destination for each workload on a case-by-case basis.

The hybrid approach is seen as winning because it allows companies to get the best of both worlds. On one hand, the public cloud offers elasticity and advanced services (e.g., AI, Big Data) without high upfront investments; on the other hand, on-premises resources provide stable costs, low local latency, and full sovereignty.

Many companies, for example, keep variable or experimental workloads in the cloud, benefiting from pay-per-use, while running stable and predictable systems on-premises, thus optimizing overall TCO.

As IDC analysts point out, the repatriation phenomenon is not an “all-or-nothing” scenario: only 8–9% of companies are considering a full return to on-premises, while the vast majority are repatriating only specific components (data, backups, particular applications) within hybrid architectures.

In practice, hybrid architecture allows each workload to be placed in the most appropriate environment, based on cost, compliance, and performance requirements, without sacrificing the scalability of the cloud where needed.

A crucial element for managing hybrid environments will also be the evolution of cross-cloud orchestration and management tools.

Gartner predicts that “cross-cloud” integration frameworks will become widespread, enabling resources across different clouds and on-premises to work together, especially in response to new AI and distributed data analytics requirements.

In other words, the cloud remains a fundamental part of the IT landscape, but it will be complemented and enhanced by interconnected on-premises infrastructures, creating a more resilient and flexible ecosystem than in the past.

5. Conclusions: Cost Control and Future Strategies

In conclusion, cloud repatriation should not be seen as a rejection of the cloud, but rather as a maturation of corporate cloud strategies.

After the initial enthusiasm for “everything in the cloud,” companies are adopting a more pragmatic and balanced approach: keeping in the public cloud what is needed (and cost-effective) and bringing in-house or to private clouds what proves costly, risky, or suboptimal.

The main driver of this shift is the need for better predictability of IT costs. Owning servers or using colocation solutions involves fixed or at least predictable expenses, in contrast to the variable cloud bills that can bring unpleasant surprises.

As highlighted, on-premises and hybrid models allow companies to avoid unexpected costs and manage IT budgets with greater confidence.

For IT professionals, cloud repatriation and hybrid cloud will therefore be key topics in 2025–2026. It’s worth periodically reviewing the cost breakdown of your cloud services and asking: “Can we achieve the same results with a different, more cost-effective, or self-managed infrastructure?”

In many cases, the answer may be yes, at least for some workloads. Preparing for a hybrid world means investing in the skills and tools to manage heterogeneous environments, from reverse migration of data and applications to automation of on-premises infrastructure.

Those who can find the right balance between cloud and on-premises will benefit from optimized costs while also leveraging the scalability and innovation offered by the cloud—the best of both worlds, without compromising their business.